by Rabbi James Rudin

It has been 65 years since I earned my rabbinical ordination from Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion (HUC-JIR) in New York City. However, those six and a half decades have not diminished my appreciation of the two rabbinic mentors who symbolically escorted me to rabbinical school and upon whose shoulders I still stand.

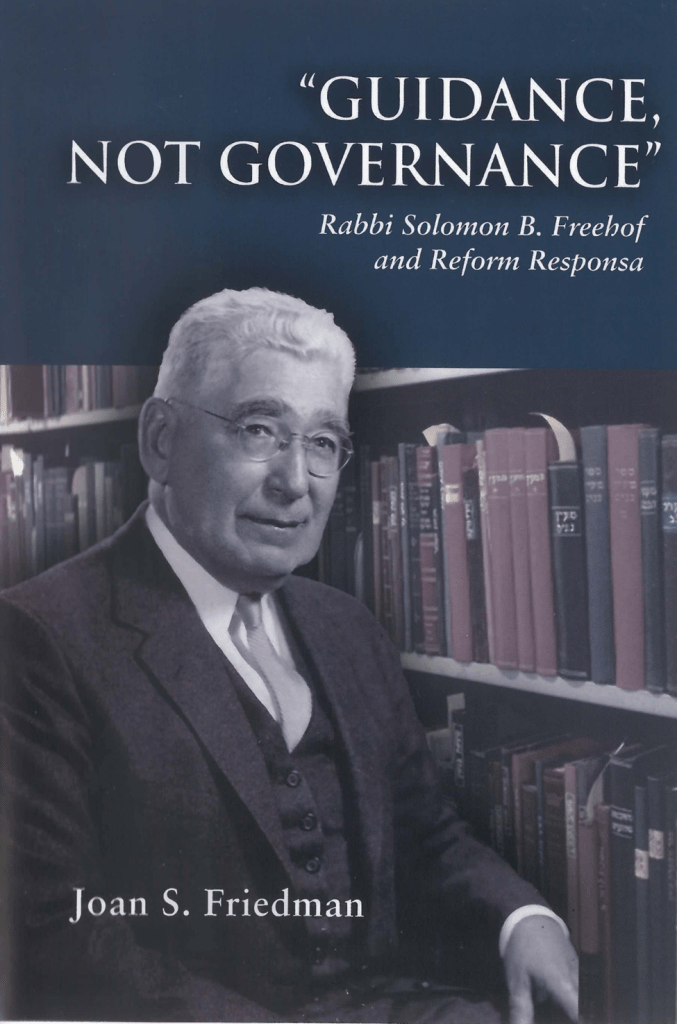

My journey began when I was six years old, a student at Temple Rodef Sholom in Pittsburgh during the fall harvest holiday of Sukkot 1940. While standing on the building’s front steps, Rabbi Solomon B. Freehof, the congregation’s senior rabbi, handed me a bright red apple to commemorate the holiday.

I proudly took the rabbi’s gift home. It was treated as a sacred object, sitting on our family’s mantelpiece for as long as nature would allow.

The following year, my father was called to active Army duty and stationed at Fort Belvoir near Alexandria, VA. We joined Temple Beth-El, the local Reform congregation. Even so, Rabbi Freehof’s influence remained strong in our home; Temple Rodef Sholom regularly sent us printed texts of his sermons and book reviews.

Even as a youngster, I appreciated his beautifully crafted phrasing, his command of Jewish sources, and how his love of Shakespeare was woven into many of his writings. During the darkest days of World War II, Rabbi Freehof always ended his sermons with realistic hope. His public book reviews attracted audiences of both Jews and Christians, numbering between 1,500 and 2,000 people.

Many years later, I visited Rabbi Freehof and reminded him of the apple. He gave me another gift: several old prayer books he had personally restored and rebound and a Passover Haggadah published in Nazi Germany in the fateful year 1938.

Rabbi Freehof was a superb interpreter of Jewish responsum, offering rabbinic answers to questions that provided guidance about Jewish customs, liturgy, ceremonies, and the adaption of traditional values in the modern world. His mastery of traditional texts allowed him to shape Reform Judaism to meet modern challenges by asserting his teachings were “…not governance, but guidance.”

His illustrious career included serving as a Hebrew Union College professor and president of both the Central Conference of American Rabbis and the World Union for Progressive Judaism. He died in 1990 at age 97.

Here is the rabbinical legacy that Rabbi Freehof bequeathed to me:

Always be meticulous in your preparations for public presentations. Take your audience seriously and never attempt to “wing it.” Offer authentic, realistic hope to people, and never underestimate young children’s powers of memory.

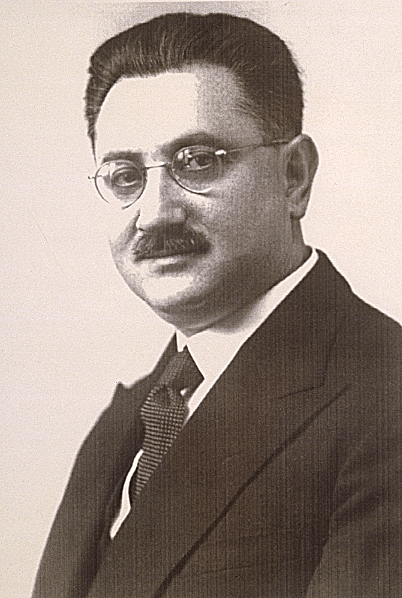

image: Rabbi Hugo Schiff, Ph.D.

Rabbi Hugo Schiff, Ph.D. was the spiritual leader of Beth El Hebrew Congregation in Alexandria, VA. Doctor Schiff had been the rabbi of a thousand-member synagogue in Karlsruhe, Germany. In 1939, he and his wife, Hannah, were rescued from Nazi Germany. He had been sent to the Dachau concentration camp near Munich in November 1938 following the anti-Jewish attacks during Kristallnacht.

Rabbi Schiff earned a doctorate from Erlangen University in Germany; surprisingly, his thesis focused on the American philosopher, essayist, and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson. During his time in Alexandria, he augmented his meager rabbinic salary by teaching religion courses at Howard University in Washington, D.C.

Hugo Schiff was always impeccably dressed, very formal in his behavior, serious, and often humorless. But he had a laser-like intellect and revered academic study — especially philosophy and biblical texts.

My mischievous classmates and I were sometimes mean to our intimidating German rabbi. During one class, as we chatted loudly, he exploded in anger and shouted, “Children, stop smooching!” Of course, he’d meant, “Stop schmoozing!” We burst out in laughter.

Although he officiated at my bar mitzvah, I did not fully appreciate Rabbi Schiff until much later, during my first year at Wesleyan University. I was in an honors “Great Books” class, and among our readings were selections from Emerson and what my professor termed “The Old Testament.” Because my family attended hundreds of Sabbath services during the 1940s, I heard our rabbi deliver many brilliant sermons about the Hebrew Bible and, of course, his beloved Emerson.

Hearing my Wesleyan professor’s lectures on similar subjects, I quickly recognized that Dr. Schiff’s extraordinary biblical and philosophical teachings were far superior to what I was learning in college. When I later told him about this, Dr. Schiff was pleased and urged me to become a rabbi. Indeed, he played a key role in my choosing to attend HUC-JIR.

Rabbi Dr. Hugo Schiff was the personification of a dynamic and intellectually rich Jewish community that was brutally destroyed during the Holocaust. He died in 1986 at the age of 93.

Both of my mentors were immigrants. Solomon Freehof was born in London and came to Baltimore in 1903 at the age of eleven. He elevated his rich English vocabulary with an eloquent speaking voice; Hugo Schiff personified the proud German Jewish scholarly tradition. However, as a displaced refugee with a heavy foreign accent, he had a harder time finding acceptance and appreciation in his new home.

Both of my brilliant mentors had a scholarly mastery of Jewish texts and tradition combined with a deep appreciation of classic literature, and both of these attributes have impacted my teachings as a rabbi.

Rabbi James Rudin is the author of The People in the Room: Rabbis, Nuns, Pastors, Popes, and Presidents, and co-author of Why (Not) Me? Searching for God When We Suffer, as well as other titles. You can learn more about him and his books at iPub Cloud International.