by Rabbi James Rudin

Professor Gershom Scholem (1897-1982), of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and arguably the greatest Jewish scholar of the 20th century, considered himself an archaeologist. No, not the kind of person who digs into the history-laden soil of Israel, but rather one who delves into the Jewish religious tradition that Scholem described as “a field strewn with ruins.”

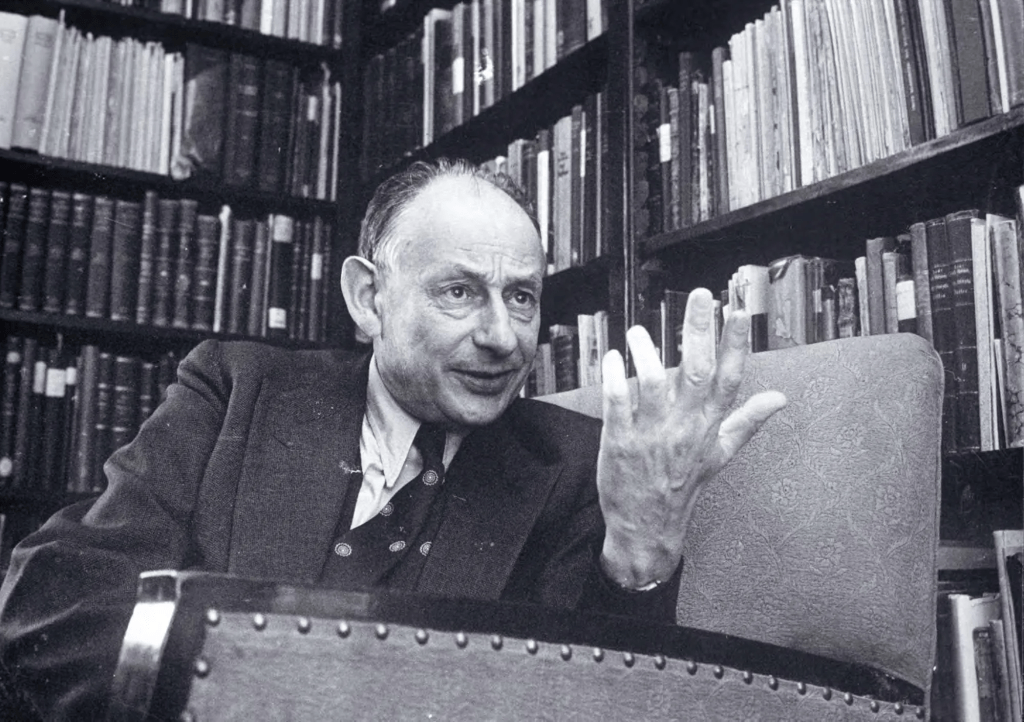

Professor Gershom Scholem. Photo credit: The Paris Review

Scholem described his life’s work as “…the modest but necessary task of clearing the ground of much scattered debris and laying bare the outlines of a great and significant chapter in the history of the Jewish religion.”

And what was the “great and significant chapter” Scholem discovered? It was the dazzling, dangerous, and demonic world of religious mysticism, especially the Kabbalah.

Jewish religious leaders of the past, he argued, had deliberately buried the rich treasure trove of anti-rationalist writings and mystical speculations that focused on messianism, restoring a shattered world (tikkun olam), and gaining an intimate relationship with God unencumbered by an oppressive legal system of overbearing rational thinking.

While Scholem brought religious mysticism back into the mainstream of Judaism, he was also personally involved in the major issues, conflicts, tragedies, and triumphs of Jewish life during the last century.

Scholem, the youngest of four brothers, was born into a highly assimilated German-Jewish family in the same year that Theodor Herzl convened the first Zionist Congress. His father was a successful printer who deliberately went to work on Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish religion, and made a point of not fasting. The Scholem parents had a family Christmas tree; “a symbol of German culture,” they explained to their children.

The four sons represent a unique cross-section of pre-World War I German Jewry. The eldest, Reinhold, became a staunch German patriot. The more conventional Erich joined his father’s printing company. Werner became a leading left-wing politician and a Communist deputy in the Weimar Republic’s Reichstag during the 1920s and was later murdered by the Nazis.

Gerhard became a fervent Zionist at an early age. His Ph.D. studies in Germany contained Scholem’s translation of a twelfth-century work of early mystical Kabbalah. In 1923, he left Berlin for British Mandate Palestine, renounced the pervasive German Kultur of his youth, though in later years Scholem wrote academic articles in his native language. After arriving in Palestine, he changed his first name to the Hebrew Gershom and moved to Jerusalem’s residential Rehavia section; his home until his death.

Scholem had both an active intellectual life and a complex love life, including two marriages, but produced no children. He used his cantankerous personality, charisma, and superb scholarship to permanently transform the study of Judaism by breaking the monopoly that rationalists and Talmudists had held for centuries over defining and dominating Jewish religious thought and practice.

But Scholem himself was not a mystic or a devotee of the Kabbalah. He was, however, attracted to two of the most famous false messiahs in Jewish history: Shabbatai Zvi (1626-1676) and Jacob Frank (1726-1791). The former disappointed his many followers by converting to Islam, while the latter disillusioned his supporters when he became a Christian.

One of the most intriguing aspects of Scholem’s life is his complicated, ambivalent relationships with four well-known German-speaking Jewish intellectuals of the 20th century: Martin Buber, Franz Rosenzweig, Hannah Arendt, and Walter Benjamin.

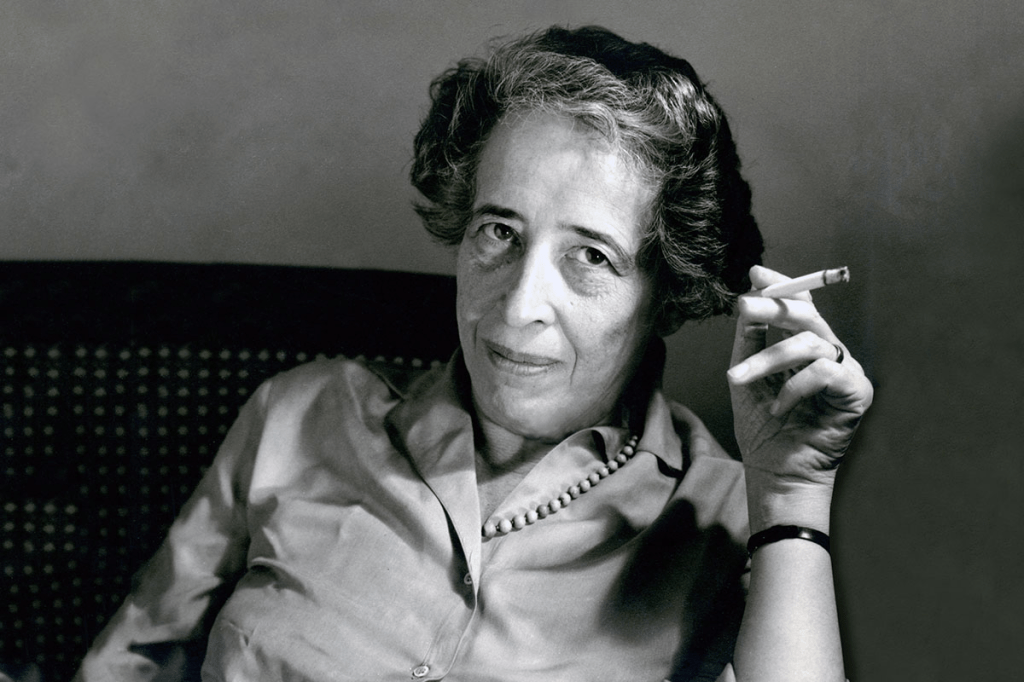

Hannah Arendt. Photo credit: The Hannah Arendt Center for Politics & Humanities

Scholem criticized Buber’s pioneering writings about Hasidism as well as Rosenzweig’s highly complex theology. Benjamin, his closest friend, disappointed Scholem by promising again and again to learn the Hebrew language and move to Jerusalem, but did neither. Benjamin committed suicide in Spain in 1940, a bitter personal loss for Scholem.

But it was Arendt, another longtime friend and a former Zionist official in Europe, who drew Scholem’s greatest private and public ire. The source of his fierce anger was Arendt’s series of writings about the Adolf Eichmann trial in Israel during the early 1960s.

When Scholem read her book, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, he erupted in bitter rage. Arendt accused Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion of staging a show trial, and she portrayed the murderous and genocidal Nazi SS leader as ‘banal.’”

Scholem charged that Arendt “lacked ahavat yisrael [love of Israel]” and as having no understanding of the inextricable relationship between the Jewish state and the Holocaust. When she died in 1975, the Scholem-Arendt break remained unhealed.

A final, more personal note: My wife, Marcia, and I heard Gershom Scholem deliver one of his last public talks at the Central Conference of American Rabbis’ 1981 convention in Jerusalem. I, of course, knew then he was an intellectual giant, and it was a memorable moment to hear the man who revived the complex but important study of Jewish mysticism.