by Rabbi James Rudin /

Header photo credit: “The sun rises over Arlington National Cemetery, Nov. 5, 2011.” U.S. Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer 2nd Class Patrick Kelley/Creative Commons

The political controversy surrounding Donald Trump’s recent visit to Arlington National Cemetery reminded me of my own visits to that sacred burial ground just across the Potomac River from Washington, DC.

I go to Section 65 in the cemetery where my parents’ grave is located and there I recite the traditional Kaddish, the Jewish prayer that is said in memory of a deceased loved one.

Interestingly, the short prayer is mostly in Aramaic, a sister language of Hebrew, and although mourners have chanted it for many centuries, the Kaddish contains no reference to death. Rather, it is a strong affirmation of both God’s grandeur and the sacredness of human life.

After the Kaddish, I always place a small stone atop the military grave that contains my father’s name, Philip Gordon Rudin, his rank of U.S. Army lieutenant colonel, the two armed conflicts—World War II and Korea— he served in, and the dates of his birth and death. On the reverse side of the grave are the name of my mother, Beatrice, and the dates of her life.

Sadly, because of our nation’s many wars, burial space for veterans and their family members at Arlington is both limited and precious. Because my father died 16 months before my mother, his casket lies 12 feet below the ground and hers rests six feet higher.

It is a long-standing Jewish custom to leave stones on a grave rather than flowers. While flowers are a beautiful gift to the living, they are like the human body that blossoms and ultimately fades. But it is believed the soul, similar to a stone, lives on forever.

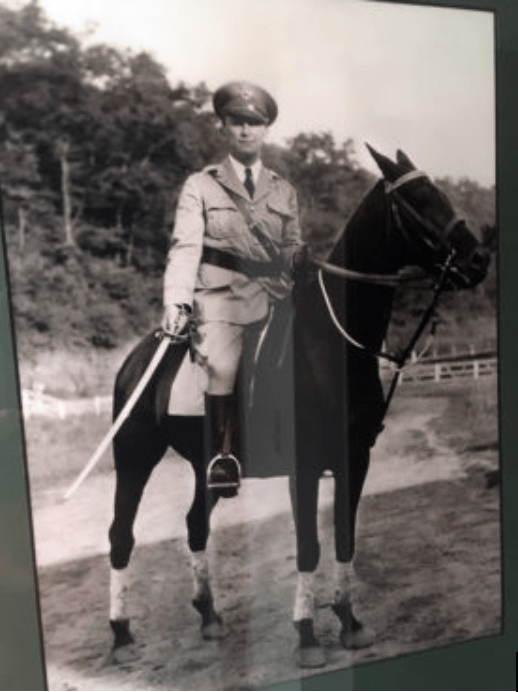

Philip Rudin circa 1939. Photo courtesy of James Rudin

Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia has a long and complex history. On the eve of the Civil War in 1861, Robert E. Lee, whose large family mansion still stands atop a hill overlooking our nation’s capital, owned the 1,100 acre area. During the war the United States government gained possession of Lee’s vast property and, perhaps as an act of wartime anger and spite, in 1864 began to bury Union soldiers on the Confederate general’s property; literally in his large front lawn.

Today the cemetery attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors each year who come to see the revered Tomb of the Unknowns, the eternal flame that guards the grave of President John F. Kennedy and his family, along with visits to the Lee Mansion and the many displays that are inextricably linked to America’s history.

But that is not all there is to Arlington National Cemetery.

Rudin family at Arlington National Cemetary. Photo Courtesy of James Rudin.

Once visitors obtain a pass to view the gravesite of a family member and walks or drives into the huge cemetery, a silence immediately grips them. The quiet is overwhelming, interrupted only by the sound of departing jet airliners from nearby Reagan National Airport.

To reach my parents’ grave, I slowly drive along Eisenhower and Bradley Avenues until I arrive at the small hill where my parents lie together eternally overlooking the Pentagon.

A visitor immediately recognizes the enormous price in military dead America has paid, and continues to pay, for our freedom and democracy. It is a sobering experience, far from the crowds of tourists with their mobile phones and cameras, and certainly far, far from the activities of daily life.

The historian Bruce Catton wrote about “The Stillness at Appomattox” following Lee’s surrender in April 1865 to General Ulysses S. Grant that finally ended the horrific American Civil War.

But there is also a precious and painful sacred silence that overwhelms me each time I visit Section 65.

I call it “The Stillness At Arlington.”

NOTE: This article has been modified from an earlier version published by Religion News Service on Nov. 10, 2019.

Jimmy, thank you so much for this…. ❤️. LeeSent from my iPhone

LikeLike

Ad usual this is beautifully and meaningfully composed.

LikeLiked by 1 person