An iPub Perspective Editorial

By Dr. Fawzia Mai Tung

I reflect on how I came to know reluctant readers – students and some of my own children! – and how I fostered a love of reading in them. This first of a two-part blog series telling the story of how the upcoming “The Wonderful Tale of Donkey Skin” came to be.

I first met a strange breed of children when I became a mother and then again when I became a teacher: “reluctant readers.” They puzzled me exceedingly because I could not understand why a child who knew HOW to read–sounding out letters, phonics, decoding, etc.—would refuse to do so when given a book.

Of course, the realization soon dawned on me that I had grown up in a completely different time and place where the most exciting thing a child could be entertained with was a book. In the crucial years between 6 and 10 years of age, I followed my diplomat father to Turkey and Saudi Arabia where we could not find bookstores or libraries carrying children’s books in French, the only language I could read at the time. So my elder sister and then I, following her example, started reading the great collection of French classics my father had collected. Jumping from children’s books such as Oui-Oui and The Model Little Girls to the non-abridged version of The Count of Monte-Cristo was rather hard, but I gritted my teeth, and soon I was carried away in Dumas’s marvelous world of adventure.

So, after we settled in Arizona and my two eldest children failed the first round of the local spelling bee, when, during the parent round, I won the whole bee, the alarm bell rang loud and clear. Something was wrong. I had already noticed that they were not exactly enthralled by the dozens of books we lugged home from the library every week. I always assumed that great readers made great spellers, as in my case, so I set out to figure out why my sons were apparently only mildly interested in books despite the overfull bookcases in our house.

I shall spare you all the different ways I tested my theories. Eventually, I landed on two campaigns to ignite the love of reading:

- Give them images first, words second.

- Start by giving them only what they are interested in.

I know some parents who will strictly forbid their children to read comics or heavily illustrated books, forcing them into chapter books with no images. This only reinforces the concept of reading as a chore or a punishment. Children love images, and who can blame them? Beautiful art is easier to comprehend than a wall of black words on white paper. Secondly, what seems great fiction to an adult may be totally boring to a child.

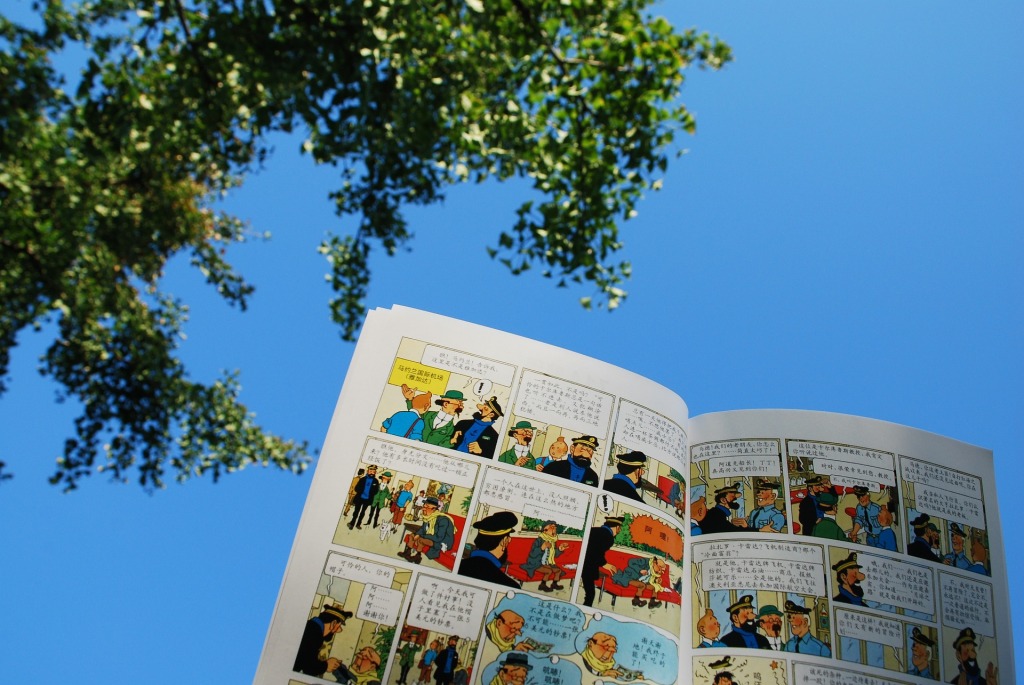

So, one might ask, what did I do? Well, to start with, I bought the entire series of The Adventures of Tintin which fascinated me when I was a child. I still love the art in those comic books—very realistic, with simple, clean lines and pastel colors. The plots were secondary to the embedded gems of humor throughout the story. The language was by no means simplistic, something I did not remember. Years later, I asked my children how the Tintin books had helped them develop their reading skills. They laughed. The first time, or even the first few times, they “read” the images only. Then, motivated to understand what was said, they would start reading the bubbles with just one or a few words in them— “Hello!” or “Help!” or “Bye!” Then, they would re-read the books by attacking the bubbles with one line of words. Eventually, they would read all the words, and the book would be in tatters. Over the years that I raised my seven children, I re-bought the entire series maybe three times. By then, the children all loved reading and kept winning spelling bees.

Of course, I am not only crediting Tintin for achieving this result. I used all the tools of the trade: daily sessions of reading a classic novel with all the children snuggled on my bed, making little books of their own, writing journals, finding movies of the book, or even better, musicals. One year, after reading the non-abridged version of Les Miserables, I bit the financial bullet and took my four youngest to see a stage production of the book. I certainly did not expect the house to be filled with songs from Les Mis for at least five years afterward.

By the time I became a school principal, I had my weapons ready. I was stunned to find many reluctant readers in much worse shape than my own children. Some of them actually hated reading. They would do so only for homework’s sake, or rather, for getting a grade. Another method that works well in the classroom is making the students take turns reading from the book, especially for conversations. I remember once making a child repeat the one sentence he had to read at least ten times (of course, without shaming him for poor fluency). I turned it into an acting exercise. “Oh, but this is a whiny little girl. You are saying this too politely. No, no, no. Do it this way …” And, I would act out in my whiniest voice. At first, the child repeated the sentence very formally and dully. Eventually, as I would not let him off the hook, he lost patience and acted so well that the whole class burst into laughter. I clapped and praised his “reading,” which, of course, was very fluent by then since he’d repeated the same thing a dozen times.

At that time, I had taken the Spalding II training (a method for teaching language arts) and could now put the correct names on what I had previously identified. We, as literate adults, do not decode when we read. We take in the image of a word, or group of words, and assign it a meaning. This is why we often misread text that does not say what we expect it to say. We could be reading the story of Snow White, and in our head think something different than what is actually written. We could be wondering how the king could have married a witch and never have known what she truly was. What happened to the king anyway? Where was he all this time? Then again, why was the queen so obsessed with beauty? And so on and so forth. These thoughts are called metacognition, or higher level thinking. Little children are not usually taught to think at this higher level, only to read a word at a time. This is why a child could read a whole sentence and then look blank when you ask him about the meaning of that sentence. What we need to do is free the child’s mind of the chore of “reading” a word or sentence and allow that mind to fly out and discover new meanings.

Images do that. They convey the plot immediately and allow the child to think around it. Reading with a child does that, too. You are free to stop anywhere and discuss ideas around the text. When the child has read at least a dozen books in this way, he is now ready to read on his own, thinking at a “higher level” along the way, and thus, enjoying the book.

It is unfortunate that there are so few books on the market aimed at reluctant readers. Little children are given beautifully illustrated picture books, then, suddenly, they are shifted to middle grade books with only a single colored illustration: the book’s cover. When later they move to young adult books, even cute little drawings disappear. One of the things that really helped me read those Little Pink Library and Little Green Library books for French-speaking children over half a century ago was the insertion of full-color illustrations every so many pages. Why do you think graphic novels have become such a trend? Our brains love images.

I hope that more writers will target this important niche. We do want the next generation to enjoy reading, right?

Look out for Part 2 of this post coming soon! “The Wonderful Tale of Donkey Skin” (ISBN 978-1-948575-60-7) will be published in May. Order your copy here and download free resources here! Featured photo by Sofía López Olalde from Pixabay.